Deer in the Forest. Painting by Eugen Krüger, Germany, 1832-1876. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Click here for high-resolution version.

I’m about three quarters done with William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich.

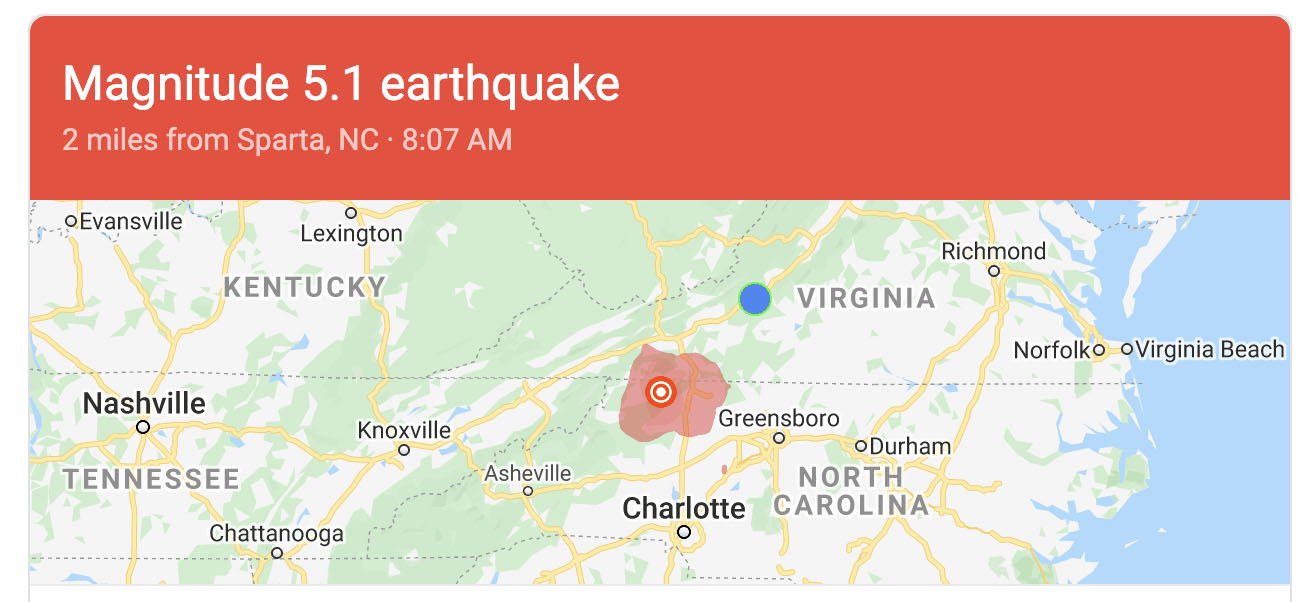

On April 9, 1940, Hitler’s armed forces started their attack on Denmark and Norway. Tiny Denmark fell quickly. Norway had the means to fight, and forests in which to hide. With Oslo under attack, the King of Norway and the members of Parliament left Oslo on a special train for Hamar, 80 miles to the north. Twenty trucks headed north with the gold of the Bank of Norway, and three more trucks with the secret papers of the Foreign Office. “Thus,” writes Shirer, “the gallant action of the garrison at Oskarsborg had foiled Hitler’s plans to get his hands on the Norwegian King, government and gold.”

The Norwegian Parliament actually met at Hamar, with only five of its two hundred members missing, writes Shirer. But when they heard that German troops were approaching, they moved again, this time to Elverum, a few miles from the Swedish border. The Germans sent a negotiator to talk with King Haakon VII. The king received the negotiator, but the negotiator was told, “Resistance will continue as long as possible.” Hitler was angry. On April 11, the German air force was sent “to give the village of Nybergsund [where the king was hiding] the full treatment.”

Shirer writes:

“The Nazi flyers demolished it with explosive and incendiary bombs and then machine-gunned those who tried to escape the burning ruins. The Germans apparently believed at first that they had succeeded in massacring the King and the members of the government. The diary of a German airman, later captured in northern Norway, had this entry for April 11: ‘Nybergsund. Oslo Regierung. Alles vernichtet.’ (Oslo government. Completely wiped out.)

“The village had been, but not the King and the government. With the approach of the Nazi bombers, they had taken refuge in a nearby wood. Standing in snow up to their knees, they had watched the Luftwaffe reduce the modest cottages of the hamlet to ruins. They now faced a choice of either moving on to the nearby Swedish border and asylum in neutral Sweden or pushing north into their own mountains, still deep in the spring snow. They decided to move on up the rugged Gudbrands Valley, which led past Hamar and Lillehammer and through the mountains to Andalsnes to the northwest coast, a hundred miles southwest of Trondheim. Along the route they might organize the still dazed and scattered Norwegians forces for further resistance. And there was some hope that British troops might eventually arrive to help them.”

On April 29, Shirer writes, they were taken aboard a British cruiser and were moved to Tromsö, far above the Arctic Circle, where they set up a provisional capital. Eventually German troops got to them, though, and on June 7 King Haakon and his government were taken to London, where they remained in exile until the end of the war.

I wonder if there is a movie about this. If not, there ought to be. The idea of a King and a parliament hiding in the woods to escape a burning village, then fleeing through a rugged valley and mountains, is exceedingly dramatic. These images stuck in my head for days, and, as I thought about it, I realized that there is a long history of hiding in the forest.

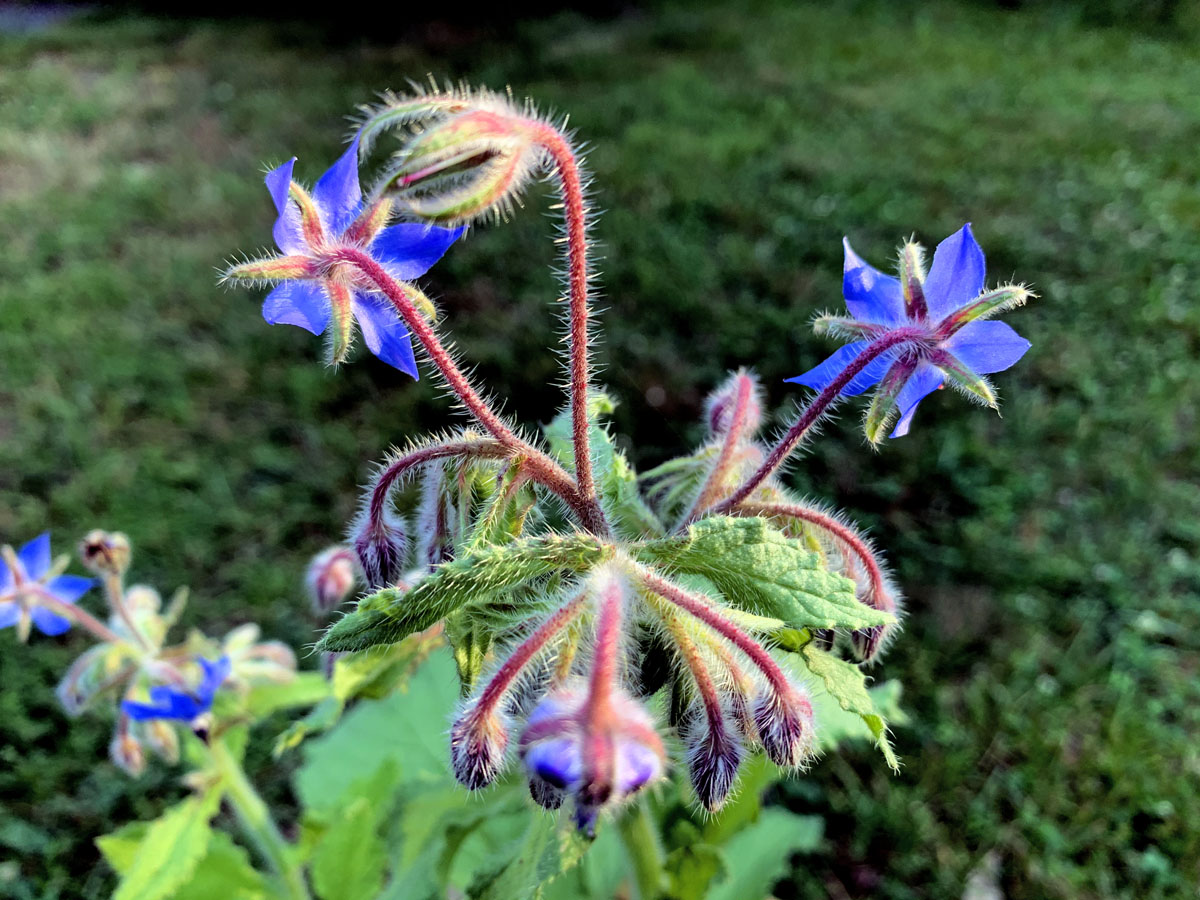

Sometimes it is good guys hiding from bad guys. Sometimes it is bad guys hiding from good guys. In reality as well as in stories, forests are a refuge and redoubt (think Robin Hood). But also in reality and in stories, forests are a dark place of danger (think Mirkwood, or Hansel and Gretel). This polar tension between forests as refuge and forests as dark and dangerous places makes them a powerful idea in the human psyche.

Very few newspaper articles stick in my mind for years, but this one did. It’s from the New York Times, with the headline “Why We Fed the Bomber.” The bomber the headline refers to is Eric Rudolph, a North Carolina (!) terrorist (anti-gay and anti-abortion) who planted a lot of bombs between 1996 and 1998. For years, he hid out in North Carolina’s Nantahala Forest, by, according to Wikipedia, “gathering acorns and salamanders, pilfering vegetables from gardens, stealing grain from a grain silo, and raiding dumpsters in Murphy, North Carolina.”

Or consider the Russian family that lived in the wilds of Siberia for 40 years, unaware of World War II. Or consider the Vietnamese soldier who hid in the jungle for 40 years. Or Barry Prudom, a murderer who hid in Dalby Forest in northern England.

In Googling for this post, I found a huge amount of material — more than enough for a book, a book that I would very much like to read, if someone would write it. It seems that the Germans, in particular, have preserved a fascination with the forest. This article, “The Myth of the Wild German Forest,” contains some excellent bits of history:

“Publius Cornelius Tacitus, a famous Roman senator and historian, was the first to write about the forests in the land of the ancient Teutons, a Germanic tribe. His brief study Germania founded the myth of the eerie forest that housed barbarians and robbers alike — a forest so dense that it helped the Teutons keep the Romans off their backs…. The forest is still today regarded as a symbol of German identity, celebrated over the centuries by poets, writers and painters. Other European cultures that also have dense forests have a more distanced relationship to their woodlands.”

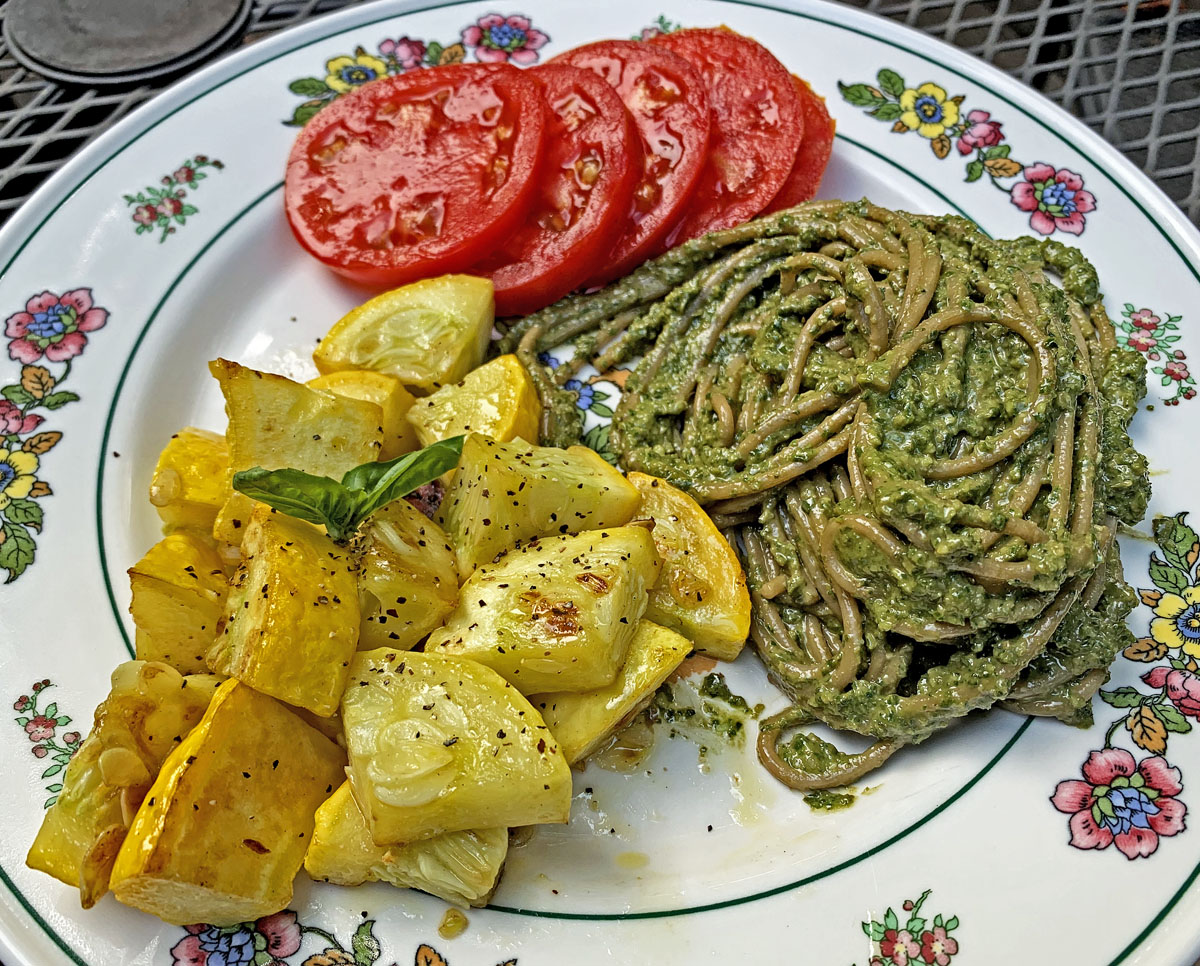

I would quickly become disheartened if I wrote here about the American attitude toward its forests. But certainly we do still have them, if we can keep them. A book that I reviewed here a few years ago, Ramp Hollow: the Ordeal of Appalachia, mentions that the early subsistence settlers of the Appalachian Mountains very much depended on the forests for their survival. From that book I learned that you don’t necessarily have to have a pasture to keep a cow. You can keep a cow in the woods. In fact, this article from Cornell University recommends keeping cows, sheep, and ducks in the forest. The article calls this “silvopasturing.”

When I was looking for land, before I bought the abbey’s five acres of woodland, I did not at first realize how much I wanted woodland. Anyone who has had supper with me out on the rear deck, when the wind is blowing, has heard me say: “Just listen. The wind in the trees sounds just like the sea.” The sea and the forest — both deep, dark, vast, mysterious, and dangerous — are closely connected ideas in the human psyche. Think of the magic of a path in the woods, especially if you don’t know who or what made the path, and you don’t know where the path is going. Tolkien invokes this idea, with great effect. I don’t think I’d be able to live in a place without either the sea or the woods.

I very much feel here that tension between the two faces of the forest: the forest as an eerie, dangerous place; and the forest as a place of refuge, where one can even find food and water. I confess that, those few times that I’ve had to venture into the woods alone at night (to look for a chicken who didn’t show up at bedtime, for example), I’m scared, and I have to buck myself up for it. Even inside the house, the nighttime noises can be scary: the alien hooting of a barred owl, or a pack of coyotes on the ridge, the snorting of a buck, or — worse — the sounds you can’t identify. My friend Ken, who doesn’t like herds of cows much more than he likes grizzly bears, has written about the primal importance of living in a place where there are things that are a bit scary. And yet, in the light of day here, when the birds are singing, I’m like the raccoons and deer: the woods make me feel safe.

It took me a while to realize that, because of my last and very difficult year in San Francisco, I developed a genuine case of post traumatic stress. It was a number things: a house fire in an old Victorian (the San Francisco fire department saved my dog, and I subsequently moved), some middle-sized earthquakes, the lingering uneasiness of feeling that cities were under attack after 9/11, the backstabbing and dirty dealing that accompanied the merging of the staffs of the San Francisco Examiner and the San Francisco Chronicle, and, probably worst of all, a water accident that occurred in my fancy fifth-floor apartment that flooded the apartments below me all the way to the basement. There was a huge fight over insurance, and not until the statute of limitations ran out did I finally feel safe from the threat of having my retirement destroyed by lawsuits (and probably bankruptcy). During that last year I had a recurring dream in which I had to cross the entire United States from west to east, skulking through the woods — always the woods — traveling only at night, and keeping away from the yellow lights of settlements and barking dogs. Eventually, in those dreams, I came to an abandoned house deep in the forest. Sometimes the place was almost grand; sometimes it was a hovel with a rotting roof and rotting floors. It was the refuge that I was looking for.

And now, this is that place.

If I built enough fence to surround four acres of woods, I could even have a cow.

Update: Ken has emailed me with the names of two movies, one about the King’s flight through the forests of Norway, and the other about a similar winter journey during the same period.

The King’s Choice (2017)

The Twelfth Man (2018)