Babel: Or, the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution. R.F. Kuang, Harper Voyager, 2022. 546 pages.

I almost never read bestsellers, and this book reminded me why. This book makes me want to go read some Jordan Peterson or something to wash the politically correct taste out of my mouth. Please don’t misunderstand me. My own liberal political views would almost surely be classified as 100 percent politically correct. But that doesn’t mean that I think that political correctness makes for good literature. Do we really need to be harangued and hectored about what we already know? There’s something insulting and condescending about that.

R.F. Kuang’s harangues in Babel: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution, are about capitalism and British imperialism. Good grief. Isn’t it about 150 years too late for that? Then again, make that 250 years, because writers should be ahead of their time, not behind.

There was another clue that I should have checked in advance before I bought this book or spent umpteen hours reading it. That’s the rating that Babel got on Goodreads, a wretched hive of mean and mediocre-minded readers if there ever was one. Truly good books (if they get read at all) will almost always get marked down by vindictive readers ganging up to push a book’s ratings down if the book contains the slightest whiff of heresy. Goodreads doesn’t think very highly of heresy or boat-rocking. Whereas books like Babel will get mostly 5-star reviews from the hive. Babel would be boat-rocking only if Charlotte Brontë had written it, when Victoria was on the throne.

R.F. Kuang is a good writer with, obviously, a remarkably good education and many interesting ideas. But that’s no guarantee that she can write a good novel (though she can write novels that are guaranteed to get published). Sure, the world is still dealing with the consequences of British imperialism and slavery. But we know that. A novelist’s job — particularly a scholarly novelist like Kuang — is to be on the leading edge, not to grind (at great length — 546 pages) a very old axe. What could she add to what ahead-of-their-time scholars have already written?

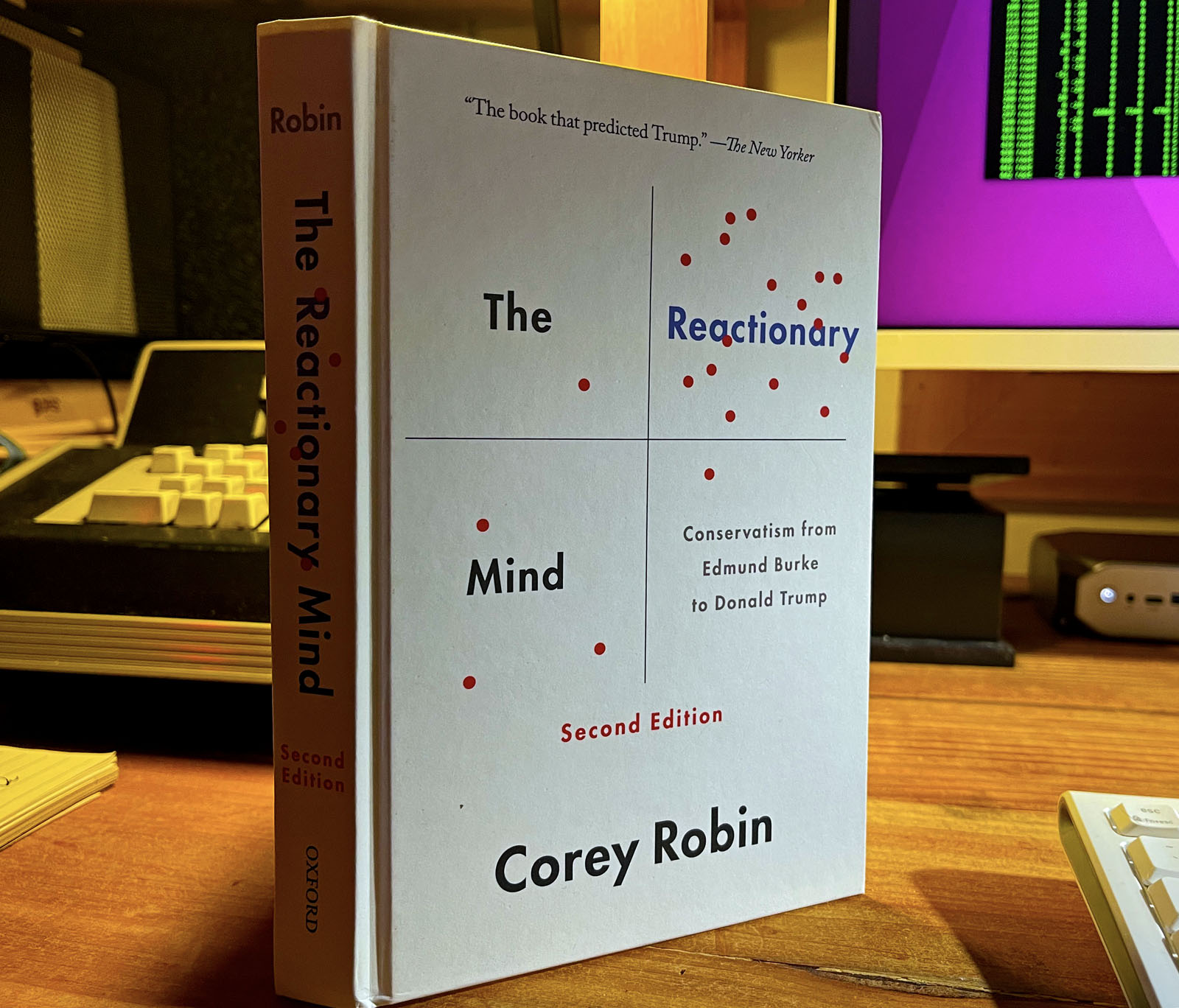

As for the mediocrity and vindictiveness of Goodreads, check out some of the 1-star reviews of, say, Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, or John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice, both of which rocked the boat a little too hard. Kuang’s Babel has a higher Goodreads rating than either of them. Babel also got a slightly higher Goodreads rating that Alice Walker’s The Color Purple (1982), which rocked the boat too much for mediocre readers and told us things that some people weren’t ready to hear. The Color Purple was not, as far as I can determine, a bestseller, and it’s on a list of the 100 books most frequently targeted for bans. Alice Walker was brave and heretical. Books like Kuang’s just invite approval.

Kuang’s characters are really very sweet, though. The atmosphere she stirs up in old Oxford is appealing. Some of her asides on linguistics are very interesting. But would you be surprised if I told you how diverse her four main characters are? One is Black, one is Chinese, one is an Indian Moslem, and one is white. The white character’s cluelessness is a foil for the what the other characters say to educate her.

Though, as I said, Kuang is a good writer, I think she lost control of this novel. Three-quarters of the way through, the dialogue loses it polish and the plotting grows careless.

But the greatest weakness of this book is plain old failure of imagination. All the gothic frills of fantasy are present, but all that remains underneath that is a rant and a harangue with no new insights. And not a whiff of heresy to redeem it.